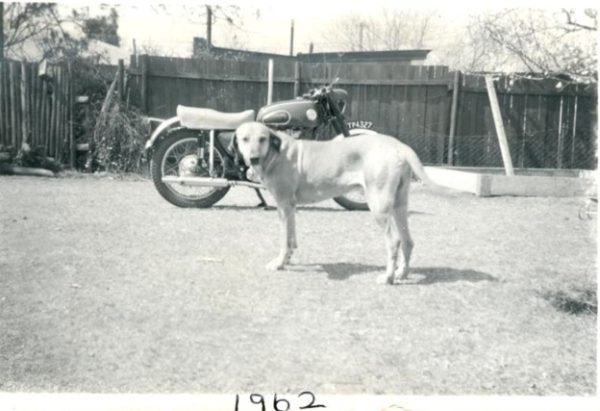

The classic black-and-white picture always summons a sense of tender nostalgia in us. And this is the case for Gary Crisp, Sequana’s Chief Engineer, who shared a photo from his childhood in South Africa. While the subject of the photograph might have originally been the motorbike – an Ariel Twin – with the family dog, Dannyboy lovingly photobombing, in the background on the righthand side is the very first Gary Crisp water pipe, built in the family’s sand pit.

At this age, most of us were attempting to assemble clumsy sandcastles for our parents to congratulate us on with blind affection. But Gary’s imagination and talent were already bursting with confidence. He was sure of one thing – one day, he would become a water engineer.

“I wanted to be a water engineer from the age of five. I loved dams, and still do,” commented Gary.

Gary and his four siblings were raised by a supportive mother who, prior to the arrival of her first child, was a qualified teacher. She encouraged them to believe in themselves and to become great at whatever they wanted to be in life. It’s with great pride that Gary shares, “All five of us Crisp children were encouraged by our mother to think about our future careers from a young age – in fact – before age 10, we’d all declared a profession, which, surprisingly, we all became. She never cared about the prestige of a job, only that we became good at it.”

This ongoing uplift gave Gary a platform to realise his dreams and dive into the complex world of desalination and reused water.

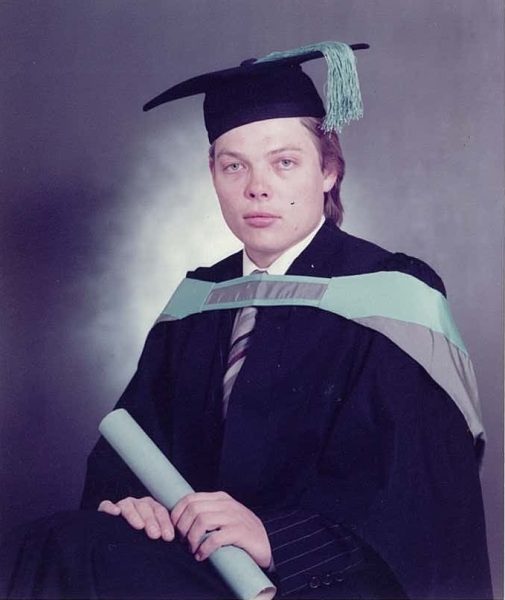

After stating his intention to become a water engineer and despite being slightly more mechanically minded, after high school, Gary undertook a BSc. Engineering (Civil) – in his second language no less – at Pretoria University, South Africa. Following graduation, he spent two years conscripted to the Air Force, where he designed and built a runway.

It was at this time that Gary would finally start his career in water engineering, employed by the Department of Water Affairs, the bulk water supplier for South Africa, initially spending three years in the hydraulics laboratory, modelling canals, tunnels and dams. A further five years were spent in dam and canal design, before Gary was promoted to the Directorate of Planning – an elite group within the Department.

Wanting to see the world (albeit on a very restricted passport), from 1989-91, Gary stepped outside of the water industry, moving to the UK for two years, starting a role as a project manager, overseeing the construction of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham. Registering as a Chartered Civil Engineer in the UK with the Institution of Civil Engineers, the world’s oldest engineering institution, with the intention of transferring his qualifications upon emigration to Australia, which he did, in 1993.

One hundred (typed and handwritten) job applications later, Gary secured his first role in Australia as a Network Planning Engineer at the Water Authority of Western Australia, however it wouldn’t be until 1998, when discovering a dusty old book that described thermal desalination, that Gary would discover his life-defining passion.

For those who discover a somewhat-niche interest (at the time, anyway), for it to grow into a passion, it helps to have a mentor – Gary was lucky enough to know the then-retired ‘Old Salt’, Alan Linstrum (dec.), who encouraged him to head to Scotland to submerge himself in the world of Scottish desalination with Weir Westgarth (now Veolia). It was here Gary would cut his teeth on Sea Water Reverse Osmosis (SWRO) desalination on the Kindasa SWRO Plant in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Gary’s return to Australia coincided with Western Australia’s move into the world of desalination – it was time to dive on in.

It’s no surprise that given his experience, Gary was the ideal candidate to be a substantial contributor to the Perth Seawater Desalination Plant (PSDP). Following the ‘winter from hell’ in 2001, Water Corporation began to investigate options to secure Perth’s water supply Gary’s expertise in desalination ensured the best technology provider was selected, with Water Corporation opting for ERI isobaric energy recovery devices. While these were largely untested at the time, they are now used in 90 per cent of the world’s large SWRO plants.

Today, the Perth Seawater Desalination Plant – on average – produces 15 per cent of Perth’s water supply and has the capacity to output 50 billion litres of water per year, continuously! Not a bad result.

Gary is now undoubtably one of the leading voices in the water industry. His active involvement with global water parties and his contemporary vision has contributed to the delivery of significant projects within the desalination and water reuse sector. Conscious that natural resources will eventually not keep up with the global demand, Gary’s passion turned into an obsessive eagerness to try and fix the situation.

“I think where I got the head start was having a passion for desalination before anyone believed in it back in 1999, realising that the natural sources, surface and groundwater, were never going to keep up with demand.”

“With dwindling runoff, I started to push for seawater desalination after I found an old textbook by Weir Westgarth on thermal desalination in the Middle East. I was so obsessed with desal, that the late head of planning suggested I prepare the strategy for introducing desalination to WA, which I completed in 2000.”

With over 44 years of experience, 24 of those specifically in desalination and water reuse, Gary’s wealth of knowledge empowers our clients to navigate and successfully deliver complex projects. When he is asked what his proudest achievement in his role at Sequana is, Gary highlights his “local and international experience as a leading desalinator being recognised by Sequana and the opportunity this has created to support a multitude of clients achieve their water security vision.”

Gary recently became a Fellow of the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE), the highest grade of membership with an institution recognised around the world. This Fellowship provides recognition for those who have made outstanding contributions to civil engineering and society. When the 2022-2023 ICE President, Keith Howells, visited Perth last year, he heard about Gary’s contribution to desalination in Australia and subsequently invited him to become a Fellow.

“A Society established for the general advancement of Mechanical Science, and more particularly for promoting the acquisition of that species of knowledge which constitutes the profession of a Civil Engineer, being the art of directing the great sources of power in nature for the use and convenience of man,” Thomas Telford, 1828.

Before joining Sequana, Gary was a Director at the International Desalination Association, and was awarded Western Australian Professional Engineer of the Year 2007, by Engineers Australia for his contribution to desalination and water reuse in Australia

A highly regarded desalination expert, with a deep passion for desalination and advanced water treatment, Gary has prepared and presented many papers related to the field.

A self-confessed tinkerer who loves being known as someone who ‘fixes stuff and knows things’, Gary is also an inventor with three world patents – including Wobblegone, a table stabiliser and MSDS® (My S*#T Doesn’t Stink), a device installed inside a toilet cistern that removes all odours from the bowl (petition to make this mandatory in all bathrooms?)

Outside of his passion for all things engineering, Gary is the proud father of two daughters, who have supported his desalination career (or maybe they have just enjoyed accompanying their father to desalination conferences around the world)!

Gary also enjoys the sound of cicadas which makes him think of his favourite movies, “Jean de Florette” and “Manon des Sources”, both directed by Claude Berri and set in Provence, France. They are the adaptation of Marcel Pagnol’s 1963 two-part novel “The Water of the Hills”.

Water never escapes from Gary’s mind after all.